Acrylic and Ink on canvas

Sectional axonometric by hand

3.5' x 4.5'ft

This project builds upon the findings of my travels in "Architecture of Coexistence" under the guidance of both my thesis advisors Mark Anderson and Morgane Copp.

My first hand experience with the subject property-a family owned building on Bliss street-provides an advantage, offering access to its internal spatial qualities and the complex socio-economic factors affecting its preservation.

This project aims to shine light on alternative preservation approaches and the possibilities that arise when we rethink preservation beyond facade retention. Rather than limiting conservation to external imagery, the proposal preserves the interiority of Lebanese central hall houses-specifically their sectional qualities such as double heights, circulation patterns, and natural ventilation systems-elements that embody the building’s cultural significance but remain inaccessible to the public.

Rather than continuing this vertical growth, the project aims to add new connections between existing structures and densify horizontally, preserving the building’s internal spatial qualities rather than just its exterior appearance.

First, the central hall was modified by reorganizing circulation around an enhanced lightwell. The courtyard now serves as a pivotal space around which various programs evolve and connect.

Second, the ground floor was opened to improve cross ventilation between the front and the back of the house. More importantly, this intervention invites pedestrians inside, giving them access to cultural heritage that belongs to the community rather than just the building owners. This creates a rare public green space in the heart of Beirut. Finally, two external bridges were added, connecting the Rayes building to the one behind it (currently abandoned and in a state of decay).

These interventions demonstrate an approach to historical preservation that works with the existing facade while introducing contemporary elements that enhance functionality and community access.

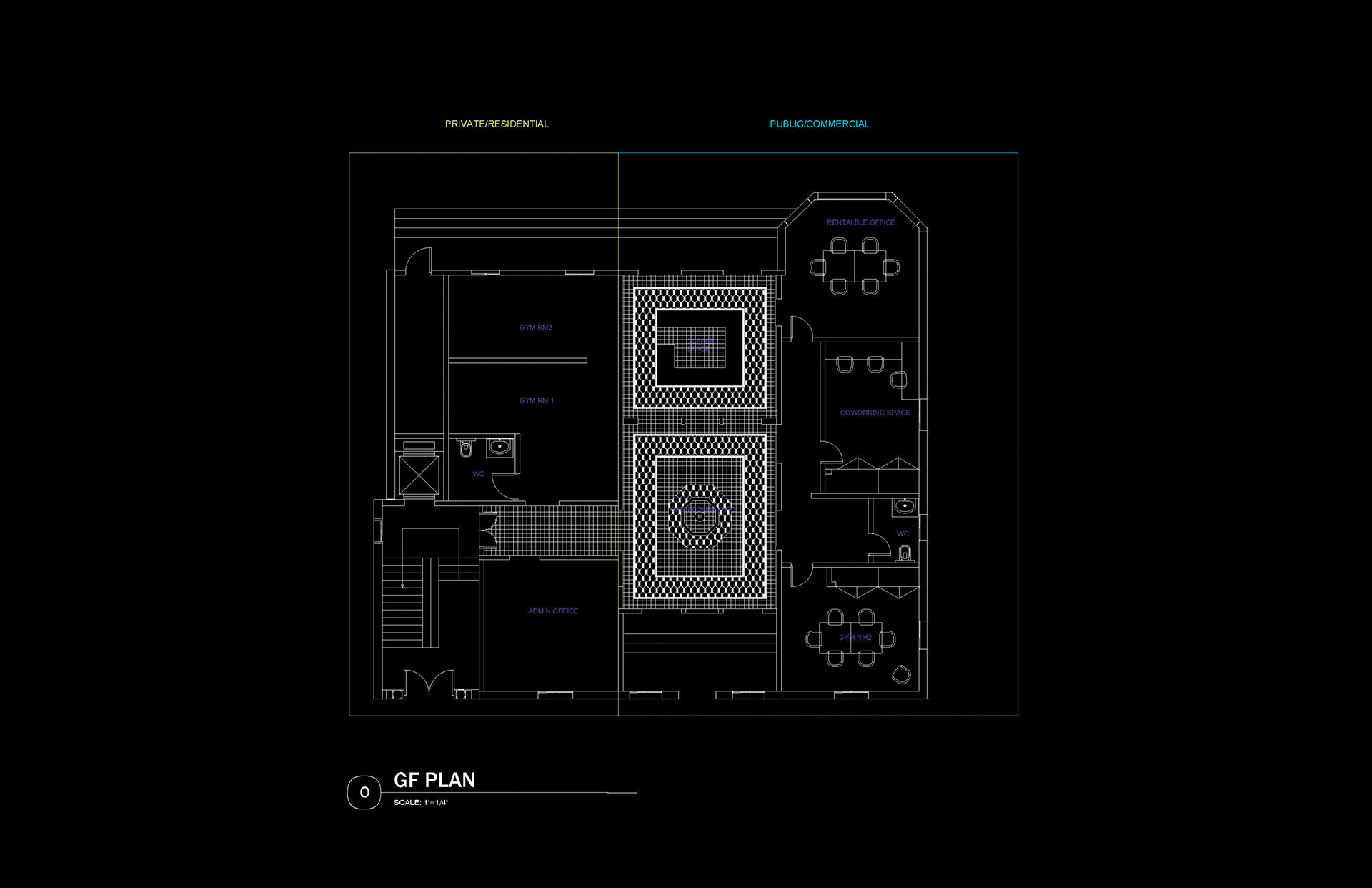

GF with an open air courtyard and access to a back garden (for both the public and residents)

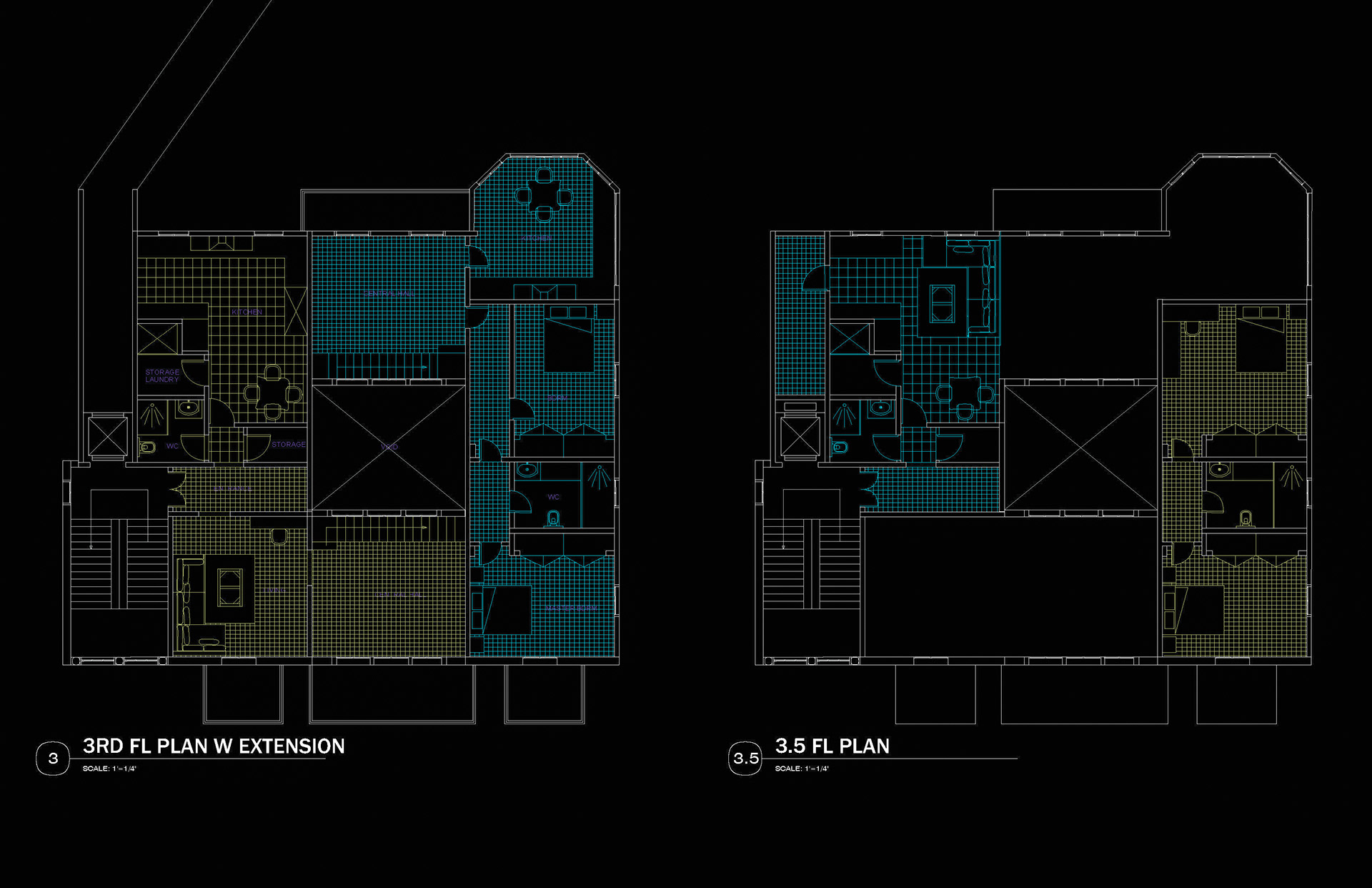

3rd Floor prototype containing 2 units instead of 1 (blue & yellow)

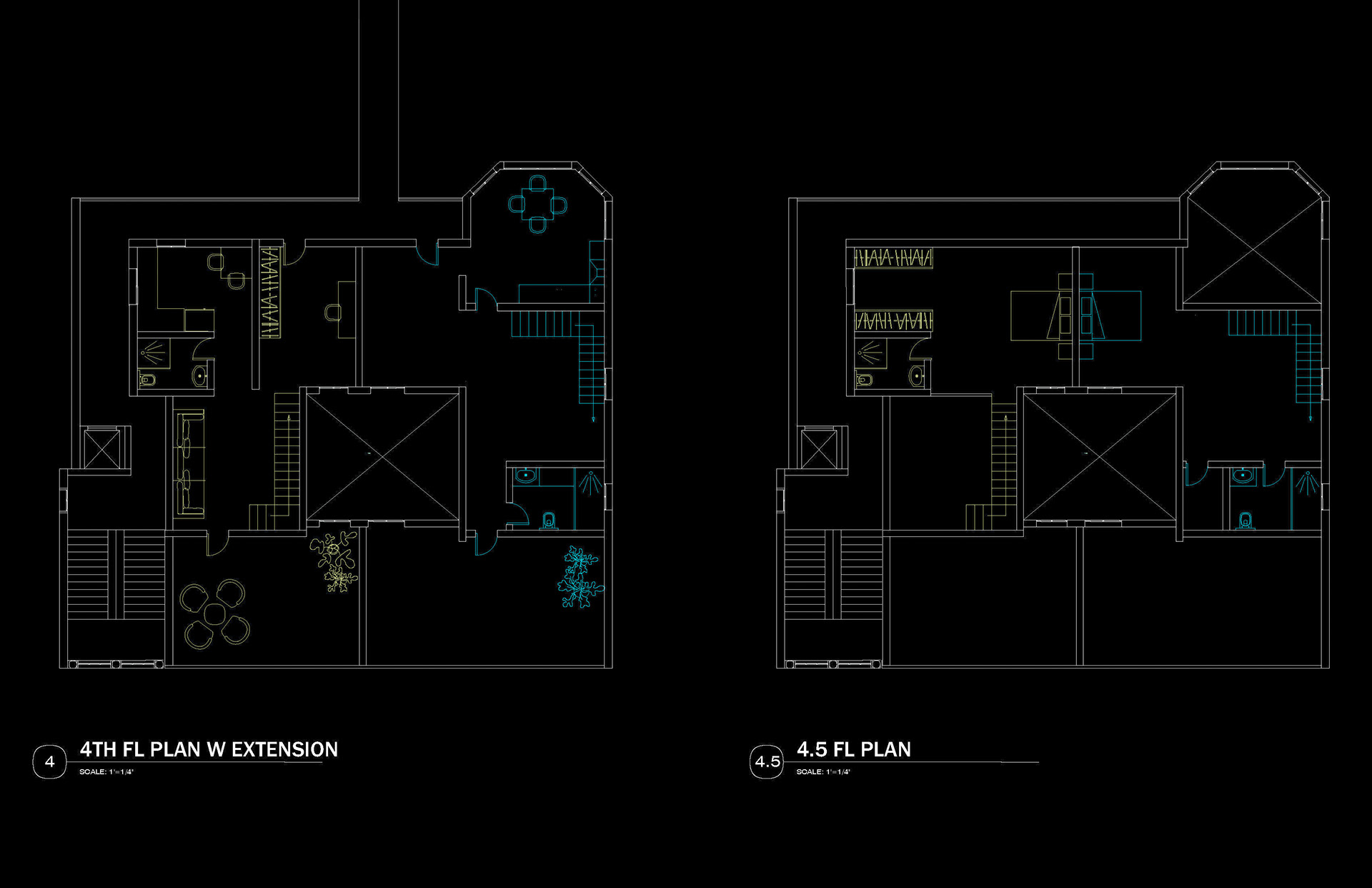

Last floor also containing 2 units instead of 1 (blue & yellow)

This is an optimistic proposal that finds beauty in decaying spaces and aims to protect them through respectful transformation that honors cultural heritage. In a city where public spaces are increasingly privatized, this approach represents a form of resistance adaptation that preserves not just buildings, but the social fabric and spatial experiences that define Beirut’s architectural identity.

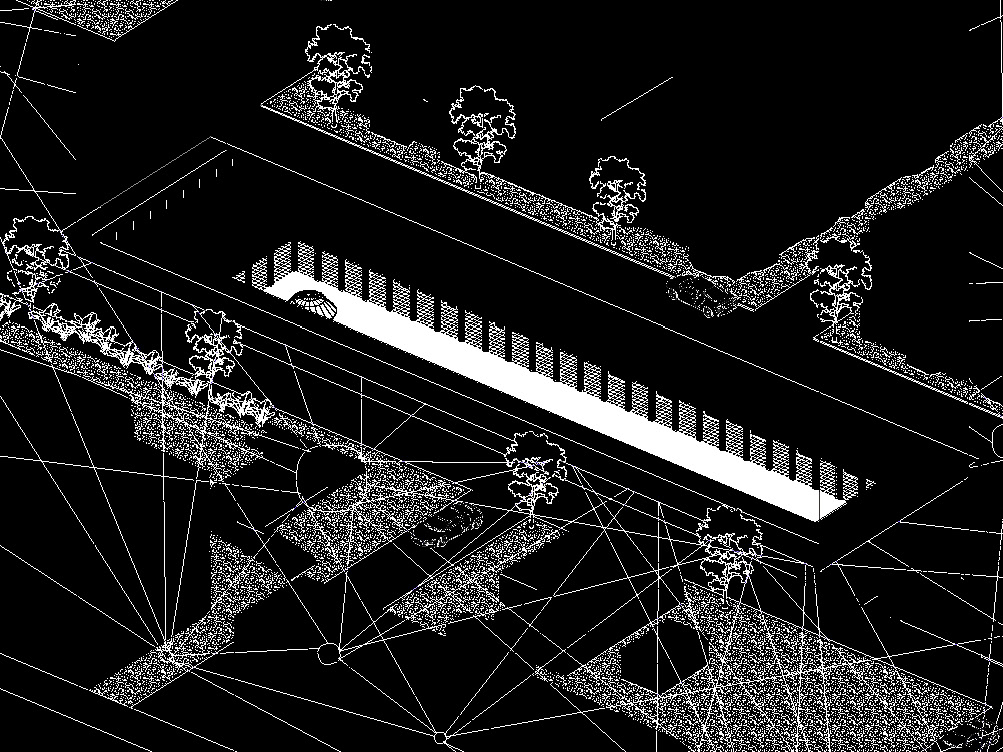

3D printed site plan of Bliss St and Mansour Jurak St

Scale 1'=1/128"

Zoom in of the site with emphasis on a horizontal densification rather than building upwards

Scale 1'=1/128"

Floor Plan of the 2nd Floor of a Liwan House (in its current state)

Scale 1'=1/4"

Physical model of the proposal to the site showing the modified 2nd Floor with interlocking units around a central void

Scale 1'=1/4"

Facade of the building after intervention (GF+1st floor only)

Interior view of the central hall that is converted into an open air courtyard (GF)

Interior of the 2nd floor of the Rayes Building (in its current state)