Branner and Stump returning fellow

The John K. Branner Traveling Fellowship and Harold Stump Memorial Traveling Fellowship are prizes for international travel and research awarded annually to Master of Architecture students (through UC Berkeley).

Dissecting the layers of Multifaceted homes:

Lebanon’s architectural narrative bears the imprints of diverse foreign influences, spanning the Roman era, the Ottoman Empire, and the French mandate. Consequently, the traditional Lebanese house emerged as a synthesis of various cultures etching their narratives onto the prototype of habitation. This undertaking aims to dissect, unpack, or deconstruct the manifold elements and layers embedded in that architectural emblem, examining how a singular house can unfurl into a multitude of residences, or how numerous homes can coexist within one.

The exploration delves into comprehending the layers and intricacies by drawing parallels, seeking to return to the origins of each foreign influence on the house. In essence, the objective is to trace each architectural element back to its country of origin, offering and sharing a profound understanding of the house’s levels and complexity.

By travelling to France (Paris), Italy (Florence/Venice), and Turkey (Istanbul), I wanted to explore specific locales that have significantly shaped the traditional Lebanese house and think of ways to counter demolition/abandonment pressures.

Photos taken by Michael Heyn of the exhibition reception at Wurster Hall (February 10th 2025)

LISBON:

Walking the streets of Lisbon I couldn’t help but notice the striking resemblance of the tiles both in color and pattern with those observed in traditional Lebanese houses. While our artisanal tiles were placed on the ground (in some homes different patterns used to indicate transitions from one space to another), Lisbon houses uses them to cover their facade to protect it from the wear and tear of salt water due to its coastal placement and its exposure to sea-salt carried by the wind.

The craftsmanship in both traditions speaks to ancient Mediterranean connections. Portuguese azulejos showcase geometric patterns strikingly similar to those found in Lebanese mountain homes. This likely stems from shared Phoenician heritage - these master traders spread ceramic techniques throughout the Mediterranean. In Lebanon, floor tiles weren’t just decorative - they served as subtle spatial markers, guiding movement through the house. A change in pattern might indicate transition from madafa (guest area) to more private family spaces.

PARIS:

The French impact on Lebanese architecture was primarily technical rather than stylistic, mainly emerging in the late 19th century with the introduction of concrete and steel construction. The French mandate period (1923-1946) accelerated these technical changes but didn’t fundamentally alter Lebanese architectural principles (form or shape.) Studying Haussmann buildings revealed parallels rather than direct influences. The long bay windows reaching to the ground, detailed ironwork of French balconies, and spatial hierarchies between reception and service areas might appear similar to Lebanese features, but these elements evolved independently. Our traditional houses developed their own sophisticated organization responding to local conditions - climate, social patterns, and building techniques. Looking at traditional Lebanese double-height spaces, I was drawn to how French architecture handled similar vertical volumes. The French doors combining entrance and balcony as one unified element particularly interested me for renovation possibilities.

MARSEILLES:

Making my way to the south, I discovered that Lebanese roofing evolved significantly. Before the 19th century, traditional Lebanese houses used diverse roofing solutions. The introduction of machine-made Marseille tiles required new construction methods, particularly imported cut timber for accurate substructures. These tiles transformed our skylines and often layered over traditional flat earth roofs to reduce maintenance.

The adoption of these red tiles marked a shift in construction and status. The new roofing needed precise timber frameworks, introducing industrial materials to our traditional building methods. This technical change reflected broader social shifts - the red tile roof became a symbol of prosperity and connection to European trade networks.

The adoption of these red tiles marked a shift in construction and status. The new roofing needed precise timber frameworks, introducing industrial materials to our traditional building methods. This technical change reflected broader social shifts - the red tile roof became a symbol of prosperity and connection to European trade networks.

VENICE:

Studying Venetian architecture revealed parallels attributed to shared conditions rather than direct influences. The similarities in stone craftsmanship, particularly in arch construction and window treatments, reflect common solutions to similar climatic challenges.

Both regions mastered the pointed arch, though with distinct applications. Venetian facades show grouped arches (a, bbb, a) breaking classical Roman regularity (a, a, a, a, a). These central groupings of arches typically used odd numbers for unobstructed views. Our Lebanese coastal homes developed similar patterns, responding to our own needs for views and ventilation.

The internal organization known as “central hall organization” also shows parallel thinking. Homes north of Venice and Istria featured a narrow corridor which iterated (as inhabitants moved south)and grew into a central halls to facilitate cross ventilation. These similarities emerged from shared environmental challenges in addition to Fakhr al-Din (a prominent Lebanese ruler) II’s 1613-1618 Venetian connections.

Both regions mastered the pointed arch, though with distinct applications. Venetian facades show grouped arches (a, bbb, a) breaking classical Roman regularity (a, a, a, a, a). These central groupings of arches typically used odd numbers for unobstructed views. Our Lebanese coastal homes developed similar patterns, responding to our own needs for views and ventilation.

The internal organization known as “central hall organization” also shows parallel thinking. Homes north of Venice and Istria featured a narrow corridor which iterated (as inhabitants moved south)and grew into a central halls to facilitate cross ventilation. These similarities emerged from shared environmental challenges in addition to Fakhr al-Din (a prominent Lebanese ruler) II’s 1613-1618 Venetian connections.

ISTANBUL:

Ottoman rule (1516-1918) influenced Lebanese architecture while preserving local systems. This period introduced elements like domes, high ceilings, and arcades, but always adapted to Lebanese climate and society.

The architectural vocabulary expanded: triple arches combining central doors with flanking windows, mandaloun windows bringing light to modest houses, muqarnas vaults showing Ottoman refinement, and arcaded courtyards serving social needs. Yet these features evolved distinctly in Lebanese hands.

Most significantly, coastal commerce transformed the traditional courtyard. As families moved to trading centers, they adapted Ottoman principles to new needs. Ground floors opened to shops while private spaces moved upward, away from the eyes of the public- a uniquely Lebanese response to changing social patterns.

The architectural vocabulary expanded: triple arches combining central doors with flanking windows, mandaloun windows bringing light to modest houses, muqarnas vaults showing Ottoman refinement, and arcaded courtyards serving social needs. Yet these features evolved distinctly in Lebanese hands.

Most significantly, coastal commerce transformed the traditional courtyard. As families moved to trading centers, they adapted Ottoman principles to new needs. Ground floors opened to shops while private spaces moved upward, away from the eyes of the public- a uniquely Lebanese response to changing social patterns.

PARIS (CONT):

During my visits in Museums, I was drawn to the interplay of enclosed and open interior spaces. The Bourse de Commerce’s glass-framed courtyard with its reflective floor, along with similar spaces in Musée d’Orsay/Richelieu and Musée Nissim de Camondo, demonstrated how interior spaces can maintain a sense of openness and light while remaining protected. These courtyards inspired thoughts about reintroducing the courtyard into coastal Liwan homes as a private but communal space, to preserve the connection to natural light while adapting to urban living patterns.

MARSEILLES (CONT):

Recommended by a local as the best spot to view Marseilles’ rooftops and red tiles, I made my way to Notre Dame de la Garde. At the top of the hill, where a massive 11-meter golden Virgin Mary looks over and protects a city that looked similar to Lebanese mountain towns. I was reminded of Anselm Kiefer’s “Fallen Angels” at Palazzo Strozzi - where an angel soars above what appears to be a burnt city. Both vantage points made me reflect on the modest scale of human intervention in our natural landscape.

VENICE (CONT'): While Lebanese architecture developed highly standardized housing designs, Venetian and Istrian buildings maintained greater variety. This architectural diversity stemmed from several factors: Venice’s preference for asymmetrical designs, irregular plot boundaries, and the unique commercial needs of ground-floor spaces facing the canals.

As for the region’s characteristic large halls with openings to courtyards or exteriors, these reflect Mediterranean cultural and environmental influences - specifically, the social nature of oriental culture, adaptation to warm weather, and the desire to balance openness with privacy.

As for the region’s characteristic large halls with openings to courtyards or exteriors, these reflect Mediterranean cultural and environmental influences - specifically, the social nature of oriental culture, adaptation to warm weather, and the desire to balance openness with privacy.

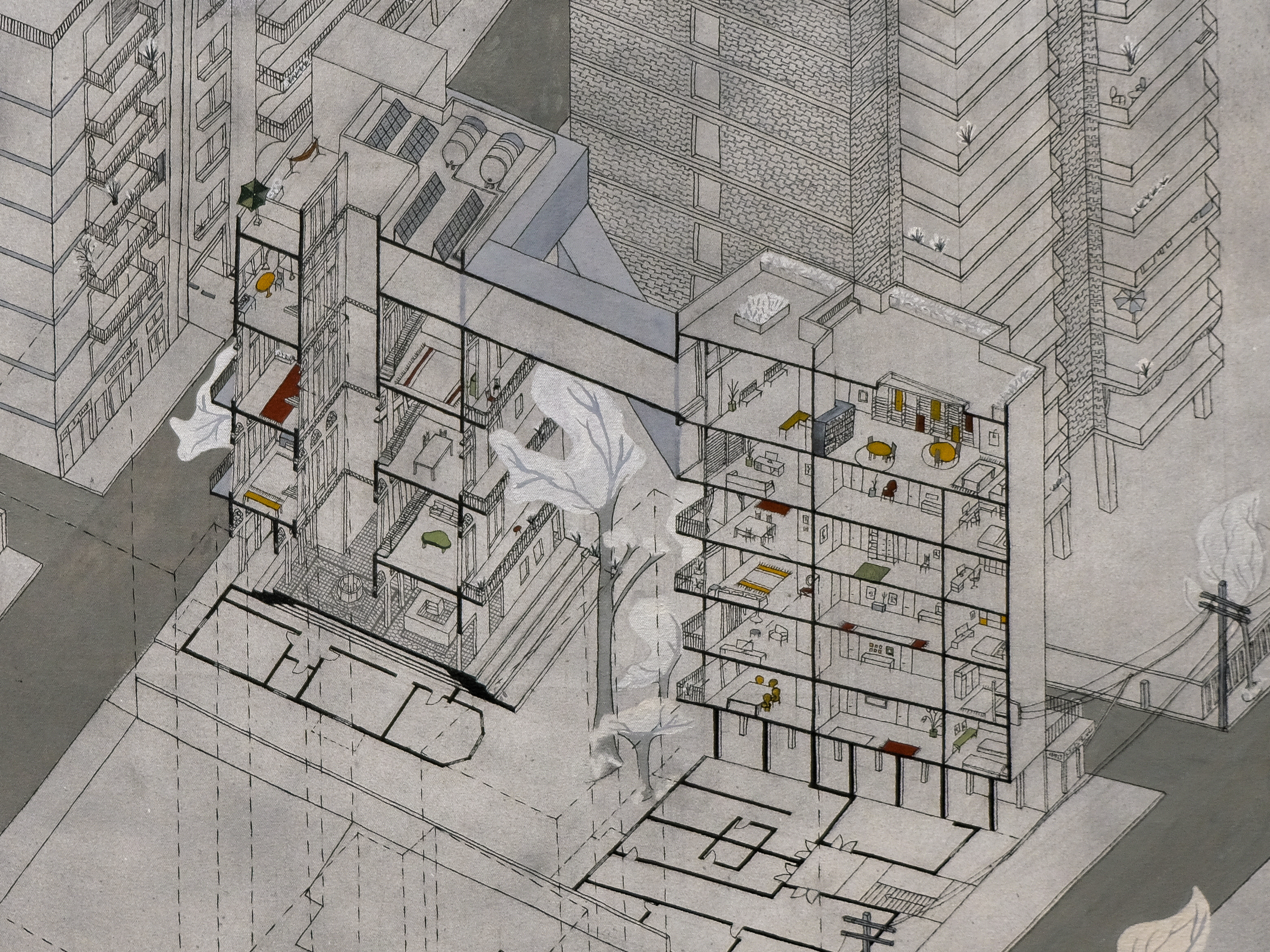

Photo of the Rayes Building, Bliss Street, Lebanon

Arriving in Beirut in July 2024, I studied the Rayes Building - a prime example of the Liwan central house type. This typology shows the integration of various influences into a distinctly Lebanese form.

The building faces preservation challenges that threaten our architectural heritage: old fixed-rent contracts drain maintenance resources, government support remains minimal/absent to homeowners, and modern family structures complicate inheritance. These pressures often lead to abandonment or in most cases demolition. The preservation challenge extends beyond single buildings to our architectural identity. Solutions must come from understanding how Lebanese architecture historically adapted to change while maintaining its essential character.

On the right you can see the floor plan of the second floor of the Rayes building in its current state/condition. It has iterated over the years with the change of renters, squatters and homeowners.

On the left is a model of the ground floor of the building. It is the beginning of a proposal to convert the ground-floor into a co-working space open to the garden in the backyard (continued in my thesis).

Photo of the physical model and floor plan scale 1'=1/4"

More photos from the trip

Istanbul

Istanbul

Istanbul

Florence

Florence

Marseilles

Istanbul

Istanbul

Istanbul

Paris

Paris

Porto

Porto

Venice

Paris

Venice

Istanbul

Florence

Florence

Florence

Istanbul

Marseilles

Marseilles

Venice

Marseilles

Venice

Venice

Venice

Lisbon

Porto

Porto

Istanbul

Istanbul

Istanbul

Venice

Venice

Paris

Paris

Venice